Every summer, our lab offers students and early-career researchers the chance to step outside the classroom and into the field, where theory meets practice, and curiosity leads the way. Whether collecting data in remote environments, collaborating with local communities, or navigating the unexpected challenges of fieldwork, these experiences provide invaluable opportunities for growth, discovery, and connection. Here are some shared firsthand reflections from some of our summer research team:

Sarah Lavallee and Tamara Donnelly

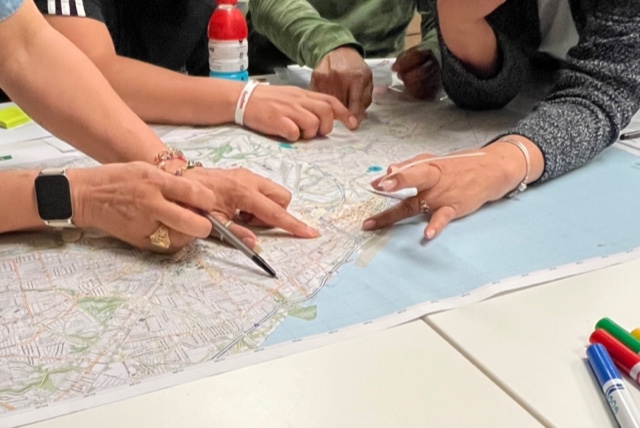

This summer, graduate students from the Social Ecology and Conservation Collaborative on the Provisioning Fisheries Project travelled to Cleveland (Ohio), Hamilton and Toronto (Ontario) to conduct field work with diverse urban fishing and foraging populations. Sarah Lavallée, MA in Geography and Tamara Donnelly, PhD in Biology, travelled to Cleveland in May for ten days to facilitate focus groups with 17 newcomers conducted in Swahili and Spanish, through the assistance of an interpreter. Focus group discussions focused on barriers to urban fishing and the use of public parks and water bodies. These focus groups included some participatory mapping where participants were asked to identify public urban spaces that they regularly visit, as well as important locations to food access (e.g. grocery stores, community gardens, etc.).

These focus groups were supplemented with shore angler surveys (n= 14) on Lake Erie and its tributaries in Cleveland to better understand the motivations and practices of diverse shore anglers. We were surprised to find that all immigrant participants in the focus groups did not fish or forage, and instead faced major constraints to their participation in these activities, including lack of time, perceptions of fishing and foraging as a high-effort-to-low-reward ratio, in addition to uncertainty and confusion regarding fishing regulations and licensing. The shore angler surveys in Cleveland revealed low female angler participation rates, but high diversity in terms of angler ethnicity.

In July, Sarah and Tamara traveled to Hamilton and Toronto to conduct focus groups with urban foragers (n=13), as part of Sarah’s MA thesis on wild foods from urban spaces. These focus groups highlighted the importance of foraging in urban spaces for cultural, social, health, and environmental reasons, despite the practice being relatively secretive. Discussions centered around themes of equity, access, sustainable food systems, and urban commons. Tea Falzata, MA in Geography, and Jessica Puistonen, MSc in Biology, joined Tamara and Sarah in Hamilton to conduct shore angler surveys and tackle shop interviews. In total, 17 shore angler surveys were completed in Hamilton over the course of two days. The shore angler surveys in Hamilton highlighted pollution as a major concern that limited fish consumption in the city.

Sarah and Tamara reflected on how their summer of field work as a team made for a positive and rewarding research experience; not only did they have a lot of fun together, but they drew on each other’s strengths and experience to facilitate meaningful research. When Sarah and Tamara were not conducting focus groups and intercept surveys, they enjoyed discovering delicious places to eat and the beautiful scenery these areas had to offer. Highlights include hiking in Cuyahoga Valley National Park, walking along the Lake Erie and Ontario shoreline, and singing along to the complete “Sound of Music” soundtrack on the long drive back to Ottawa from Cleveland.

Caraline Billotte

This summer, I had the opportunity to bridge both the social and ecological dimensions of environmental research through two distinct but complementary experiences. For my own master’s research, I focused on developing and administering an online survey designed to assess how value-framed messaging influences behavioural intentions in lake stewardship practices across the Rideau and Kawartha Lakes Region. This sociological approach, which was relatively new to me, allowed me to explore the human dimensions of conservation in a way that felt both challenging and rewarding. I was excited to engage with theories of environmental psychology and communication, and to see how values-based messaging might be applied in real-world stewardship contexts.

At the same time, I wanted to expand my skills in ecological fieldwork, and with the support of my supervisor, I joined a side project known as the Common Goldeneye Project in Fairbanks, Alaska. Alongside three other students, I contributed to a long-term waterfowl monitoring program that has been ongoing since 1970. This hands-on field experience introduced me to new ecological methods, including proper animal husbandry, bird tagging techniques, and web-tagging ducklings. I also learned how to use field equipment to identify different stages of incubation, which deepened my understanding of avian life cycles and monitoring protocols. Working directly with wildlife in this way was both demanding and rewarding, offering a very different but complementary perspective to my own research.

Together, these experiences gave me a unique summer of growth: advancing my sociological research skills while also immersing myself in ecological field methods. The balance between human-focused and ecological work not only broadened my expertise but also reaffirmed the value of interdisciplinary approaches in conservation.

Rebeccah Kennedy

Over the past year I have had the opportunity to complete fieldwork in Slave Lake Alberta working withforestry professionals as wells as Indigenous communities including: Sucker Creek First Nation, Swan River First Nation, the Lesser Slave Lake Métis District (LSLMD). Through these trips I have been able to attend community events, conduct interviews and workshops, assist with focus groups and attend culture camps. All of this fieldwork is part of the larger TRIA-FoR project that looks at how communities respond to and want to be involved in responses to forest risks.

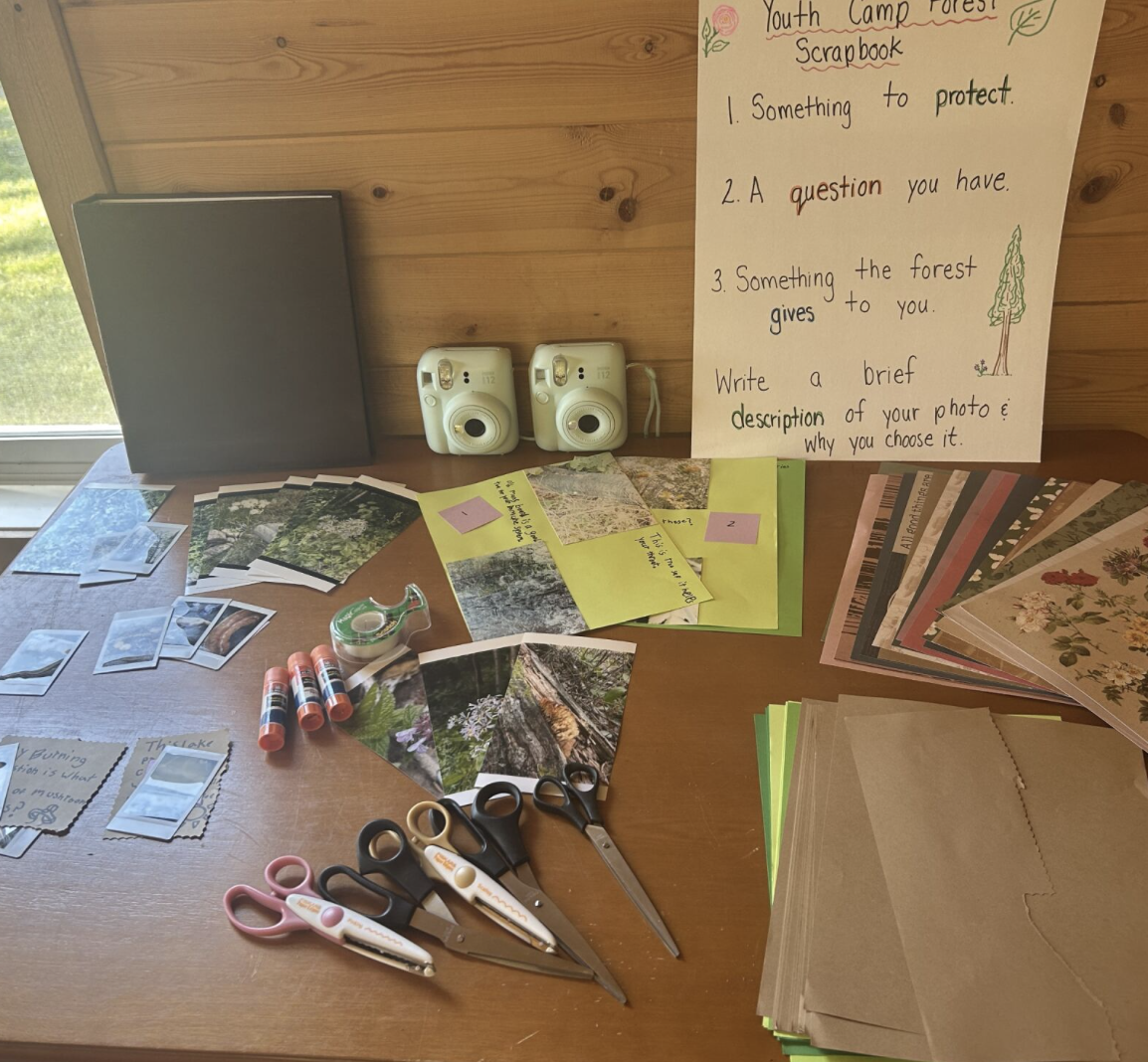

The bulk of my fieldwork takes place with the LSLMD who I have collaborated with to run communityworkshops and youth camp activities. This work would not have been possible without the support and contributions of their district office staff. At the workshops I was able to work with other team members to learn from elders and land users about their relationship with the forest and the forestry industry. I was also able to attend their youth camp where I led a Forest Scrapbook activity to explore their forest relationship. These activites gave me experience working with a wide variety of age ranges, leading discussions and also used innovative methods (including scrapbooking which used combination of photos and reflections).

While conducting my research, I was also able to participate in a wide range of community activities. These activities included jigging, storytelling, forest walks, beading, fishscale art and buffalo harvesting, just to name a few. Not only did these activities enhance my understanding of the LSLMD forest relationship and the value of understanding different perspectives, but they also highlighted the importance of relationships with the community as part of the research process. It is hard to capture how much these activities meant to my research and to myself. I thank the LSLMD community for being so welcoming to me and our team and for being open to embracing new research methods. I learned so much from everyone, and I look forward to future fieldwork!